Tribes in Afghanistan: A Guest Post from Michael Yon

It can be tempting to downplay or ignore the influence of tribes in Afghan politics, and on the effects on our operations. We tried to ignore the great influence of the tribes during the war in Iraq, and not until 2006, fully three years into the war, did we effectively begin to work with tribes on an appreciable scale.

The work with the tribes during 2006–2007 in Anbar Province helped set conditions that greatly facilitated the successes of “The Surge,” which unfolded during 2007. A compelling argument could be mounted that had we not seen the 2006 tribal “Awakening” in Anbar, the Surge might have spiraled into yet more violence, and the war in Iraq could have been lost.

Drawing parallels between Afghanistan and Iraq is fraught with peril, yet there are some useable lessons in regard to tribal influences.

As I wrote in a recent Washington Times article:

Time has a different meaning here. Take the case of members of the Baibogha tribe who abandoned a patch of land nearby about 150 years ago. Hazaras moved in, now Baibogha have come back to tell Hazaras, “Wait . . . you stole our patch of nothing while we disappeared for 150 years.”

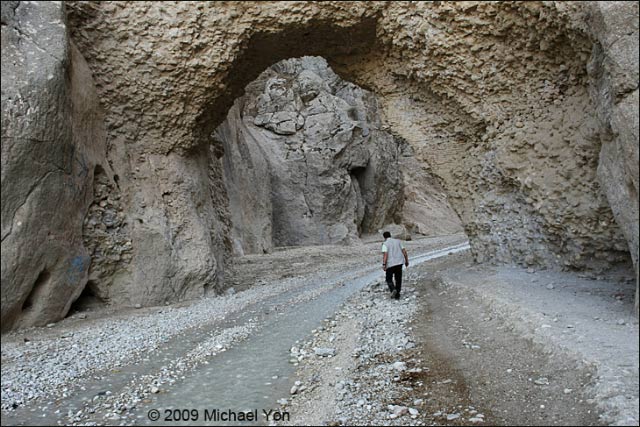

The memories are long and Afghanistan is a fragmented “country” by even the most enthusiastic interpretation of the term. The president of Afghanistan is little more than the mayor of Kabul. Government influence is no more prevalent than are paved roads. In Ghor Province, for example, there is not a single meter of paved road, and the effective law of the land falls on tribal lines.

If we desire to help bring Afghanistan to a status that a reasonable observer might call a “developing nation,” then the commitment here has just begun. This expensive project will require many decades of effort at best, and more likely a full century of commitment.

If most Afghans cooperate, and we work hard together, Afghanistan might develop into a self-sustaining country—a real country—after a few decades. In the dispatch “Sangow Bar Village” I wrote that the village was in the dark.

It had no electricity until 2006 when Lithuanians invested about $40,000 to build a micro-hydro generator with the idea of watching the village to see if true improvement was made. Today, Sangow Bar has plenty of electricity and the people have lights and satellite television . . . The Lithuanians have determined that the project was a success, and the project appeared to be a success to the Japanese and to me.

With this success in mind, the Lithuanians together with Iceland decided to build thirty more hydro-generation stations. Now, if we look at this in context of the broader picture, thirty, three hundred, or even three thousand might seem like an irrelevant number. But it’s not.

However, Afghanistan’s narco-remittance-puppet-state is hindering each attempted step forward. An embryo of a real country is growing, but will die instantly without help. For now, and at a minimum many decades to come, with a lack of stable government, tribal influences will be at least as important as those emanating from Kabul.

Michael Yon

Sangin, Helmand Province

Indeed lucky to have Michael guest post. The big question is does the West want to invest that much time and money into Afghanistan? Machiavelli tells us that in order to maintain a land that is foregin in language, culture and laws, the invader/conqueror must set up his capitol there, have the king live there or send his people to settle and colonize there. I don’t see any of that happening. What are the alternatives?

Do the outlying tribes want to be connected to Kabul? Is it desirable for them to be represented in Kabul? Can their status in the world be enhanced by a connection to the capital of Afghanistan? I’m not sure we know the answers to these questions right now. As it stands right now, this part of the world is an excellent place from which to conduct business if you’re running a terrorist organization. No one has captured Bin Laden and no one seems to be eager to turn him in either. Bin Laden seems to have hit on the right recipe for a safe haven, and we talk about decades for any real changes to take hold. My guess is that the best we can hope for, is a kind of containment. Seems like cold comfort. Nearly 10 years into it and our best hope is that maybe his recruits will start to run dry. Desperation has been a fertile soil from which to grow these raw recruits in the past. If some of the despair could be replaced with hope and stability, we might see a change. We’re talking years here, anyway you cut it.

You bring up some good points. However, I think that you have it backwards. The question isn’t whether these tribes want to be connected or represented in Kabul. It is how can we influence them to want to be connected to the government in Kabul. This is done by offering incentives. These aren’t always monetary (but usually are). Most tribal heads look to maintain their influence. After that, they look how they can expand their influence. We aren’t talking about the world stage in most cases. You have to remember that this is truly a cut throat society. No matter how good a leader is, he has to look out for himself and his first and foremost, or he will be displaced by a more wily adversary. Our ideas of graft and corruption are vastly different than what the Afghan reality is. I have spent several tours understanding this. Sometimes you have to pick the least corrupt guy to back. Other times you have to side with the guys that can give you what you want. Either way, we need to focus on engaging the various tribal elders from a position of strength. This means that we need to be in a position to elevate their monetary and influential status, if they follow the lead of the government in Kabul. This will provide the incentive to connect and defer to the government in Kabul, as well as give prestige and influence to said government. To simplify this, just think of the Sopranos. “What can I do for you Vinny”? “Don Guido, I want into the organization. I have a job planned and need your help”. “OK. It’ll cost you 30%”. “For 30% what do I get”? “You get top cover should you get pinched, and you don’t have to worry about my guys getting in your way”. “OK. 30%. sounds fair”. This is the way business is done in Afghanistan. Our government needs to realize this and accept it. If we want to change this, it will take an un-acceptable amount of time and resources. This is just the humble opinion of a grunt, knuckle dragging Special Forces guy with a few tours under his belt.

Wisner–besides all that don’t forget Alexander married Roxanne. Maybe we should ask Rick and some of his SF pals to settle down out there.

Re the idea of obtaining the tribes’ loyalty: seems to me it’s a zero-sum game; elevating or enhancing the leader of one tribe automatically puts someone else’s tribe at a relative disadvantage or loss of local influence, hence a potential enemy. Playing them off, balancing their relative strengths–this strikes me as something the US won’t take the time to do.

Finally, spending a century or so making Afghanistan into, say, Sri Lanka doesn’t seem to be in our interest. We should have something like the post-Civil War cavalry in the West, keeping control of our enemies in defined zones and letting the locals live as they wish. This strikes me as doable and realistic.

I think after this drags on a little longer we will probably cut and run as the perception is that we cannot afford the expense of maintaining a presence on the other side of the globe indefinitely.

The sheep don’t understand problems that don’t directly and immediately pertain to them, especially in dire economic situations. 10 years of war is a tough pill to swallow, and if we finish things up nicely in Iraq, we will be there for a great many years, able to project power from bases in Iraq and consequently have a bit of leverage over the middle eastern oil markets in a time of “peak oil.”

Nah, this time, in these here hinterlands, we let Geronimo (aka OBL) spend his last days among his people, rather than chase him down.