The Warrior Sense of Humor

Chapter 20 Die Laughing

The warrior sense of humor is terse, dry—and dark. Its purpose is to deflect fear and to reinforce unity and cohesion.

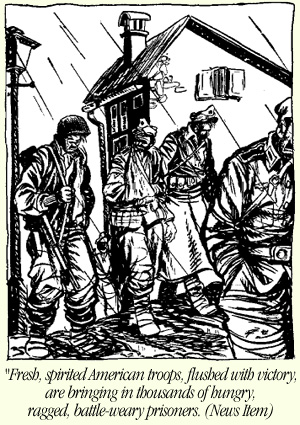

Bill Mauldin won a Pulitzer for this "Willie and Joe" cartoon

The Warrior Ethos dictates that the soldier make a joke of pain and laugh at adversity. Here is Leonidas on the final morning at Thermopylae:

“Now eat a good breakfast, men. For we’ll all be sharing dinner in hell.”

Spartans liked to keep things short. Once one of their generals captured a city. His dispatch home said, “City taken.” The magistrates fined him for being verbose. “Taken,” they said, would have sufficed.

The river of Athens is the Kephisos; the river in Sparta is the Eurotas. One time, an Athenian and a Spartan were trading insults.

“We have buried many Spartans,” said the Athenian, “beside the Kephisos.” “Yes,” replied the Spartan, “but we have buried no Athenians beside the Eurotas.”

Another time, a band of Spartans arrived at a crossroads to find a party of frightened travelers. “You are lucky,” the travelers told them. “A gang of bandits was here just a few minutes ago.” “We were not lucky,” said the Spartan leader. “They were.”

In Sparta, the law was to keep everything simple. One ordinance decreed that you could not finish a roof beam with any tool finer than a hatchet. So all the roof beams in Sparta were basically logs.

Once a Spartan was visiting Athens and his host was showing off his own mansion, complete with finely detailed, square roof beams. The Spartan asked the Athenian if trees grew square in Athens. “No, of course not,” said the Athenian, “but round, as trees grow everywhere.” “And if they grew square,” asked the Spartan, “would you make them round?”

Probably the most famous warrior quip of all is that of the Spartan Dienekes at Thermopylae. When the Spartans first occupied the pass, they had yet to see the army of the Persian invaders. They had heard that it was big, but they had no idea how big.

As the Spartans were preparing their defensive positions, a native of Trachis, the site of the pass, came racing into camp, out of breath and wide-eyed with terror. He had seen the Persian horde approaching. As the tiny contingent of defenders gathered around, the man declared that the Persian multitude was so numerous that, when their archers fired their volleys, the mass of arrows blocked out the sun.

“Good,” declared Dienekes. “Then we’ll have our battle in the shade.”

Several aspects of this quip—and Leonidas’s remark about “sharing dinner in hell”—are worth noting.

First, they’re not jokes. They’re dead-on, but they’re not delivered for laughs.

Second, they don’t solve the problem. Neither remark offers hope or promises a happy ending. They’re not inspirational. The deliverers of these quips don’t point to glory or triumph—or seek to allay their comrades’ anxiety by holding out the prospect of some rosy outcome. The remarks confront reality. They say, “Some heavy shit is coming down, brothers, and we’re going to go through it.”

Lastly, these remarks are inclusive. They’re about “us.” Whatever ordeal is coming, the company will undergo it together. Leonidas’s and Dienekes’s quips draw the individual out of his private terror and yoke him to the group.

Even the epitaph of the Three Hundred (by the poet Simonides) is lean and terse. It leaves out almost every fact about the battle—the antagonists, the stakes, the event, the date, the war, the reason for it all. It assumes that the reader knows it all already and brings to it his own emotion.

Go tell the Spartans, stranger passing by, that here, obedient to their laws, we lie.

The ancients had no monopoly on economy of speech or deadpan humor. A couple of years ago near the Habbaniyah Canal in Ramadi, Iraq, a visitor from the States came upon a squad of Marines digging a trench in 125-degree heat. Raw sewage was sloshing into the ditch; the heat seemed to concentrate and intensify the stench. To make the chore even more miserable, regulations required that the Marines wear their helmets and heavy body armor. One private seemed to be struggling more severely than his buddies. “How you doing, Marine?” asked the visitor. The private looked up with a grin and kept on shoveling.

“Living the dream, sir,” he said.

[Continued next Monday. To read from Chapter One in sequence, click here.]

Well, I always preferred the “be smarter, not tougher” mindset in this passage from Harry Harrison (“Deathworld II”, quoting from memory) :

“Better to die free than to live in chains!”

“Don’t be a bigger idiot than usual. Better to live in chains while you figure out how to get rid of them.”

;o)

Love these stories! Every decent survival handbook/guide/instructor I’ve come across states that every survival kit must include a sense of humor.

It is possible–and for me, preferable–to be professional without being serious.

After my grandfather, a world war two vet, died; I was going through his books and claimed several. Of note was a copy of Bill Maudlin’s ‘Up Front’.

Inside was brief note, the book was from my grandfather to my grandmother, to let her know how it was over there.

“Living the dream, sir.” Jesus, that’s great!

Wonderful stories! Thanks for sharing these. I knew the line about fighting in the shade was from history, but wasn’t sure how it fit into the real story, just Frank Miller’s “300.” LOL

There was a moment that I could not help remembering between Spartans and Athenians, during their war.

Athenians sent a letter to the Spartans:

‘If we win the war we will take you’re lands, burn down your houses, enslave your women, and kill your children.’

The Spartans sent the one word reply:

‘If.’

that was phillip of macedon, the athenians never sent any messages like that

and despite the spartans response they were on the losing side. it was a bluff and they lost

oohrah

“Living the dream, sir,” he said.

It is said that a picture is worth a thousand words. That one line, that “picture” was worth at least one thousand and one. That one line is the epitome of your concept …

My favorite terse, humorous (and probably apocryphal) report is attributed to British General Sir Charles Napier when he conquered the Indian province of Sind. He is reported to have wired the British War Office a one word report, “Peccavi” or “I have Sind [sinned].”

[From Latin peccavi (I have sinned), from peccare (to err).]

The retort may have been dreamed up by “Punch Magazine,” as I can hardly imagine a British general as being so witty.

I must get across my affection for your kind-heartedness in support of men and women that should have guidance on that topic. Your personal commitment to getting the solution all around has been quite functional and have constantly empowered many people just like me to attain their goals. Your personal invaluable guide implies so much to me and especially to my colleagues. Best wishes; from all of us.