The Gulag Archipelago

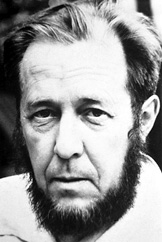

Special thanks to Tina McCann for sending in this piece on the great Russian writer, Alexandr Solzhenitsyn, author of One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich, The Gulag Archipelago, Cancer Ward and The First Circle.

Alexandr Solzhenitsyn

The post is in two sections. The first (short) one is from Solzhenitsyn’s autobiographical The Oak and The Calf. In it, he “recalls how he ‘wrote’ in the camps, where writing was forbidden—and how vulnerable his work was.”

The second section is from Solzhenitsyn’s Nobel Prize lecture. Here is an artist—and a man—who towers over just about everybody:

From The Oak and the Calf:

In the camp, this [writing] meant committing my verse—many thousands of lines—to memory. To help me with this, I improvised decimal counting beads and, in transit prisons, broke up matchsticks and used the fragments as tallies. As I approached the end of my sentence, I grew more confident of my powers of memory, and began writing down and memorizing prose—dialogue at first, but then, bit by bit, whole densely written passages. … But more and more of my time—in the end as much as one week every month—went into the regular repetition of all I had memorized.

Then came exile, and right at the beginning of my exile, cancer. … In December [1953] the doctors—comrades in exile—confirmed that I had at most three weeks left.

All that I had memorized in the camps ran the risk of extinction together with the head that held it. This was a dreadful moment in my life: to die on the threshold of freedom, to see all I had written, all that gave meaning to my life thus far, about to perish with me …

From the Nobel Lecture:

I was born at Kislovodsk on 11th December, 1918. My father had studied philological subjects at Moscow University, but did not complete his studies, as he enlisted as a volunteer when war broke out in 1914. He became an artillery officer on the German front, fought throughout the war and died in the summer of 1918, six months before I was born. I was brought up by my mother, who worked as a shorthand-typist, in the town of Rostov on the Don, where I spent the whole of my childhood and youth, leaving the grammar school there in 1936. Even as a child, without any prompting from others, I wanted to be a writer and, indeed, I turned out a good deal of the usual juvenilia. In the 1930s, I tried to get my writings published but I could not find anyone willing to accept my manuscripts. I wanted to acquire a literary education, but in Rostov such an education that would suit my wishes was not to be obtained. To move to Moscow was not possible, partly because my mother was alone and in poor health, and partly because of our modest circumstances. I therefore began to study at the Department of Mathematics at Rostov University, where it proved that I had considerable aptitude for mathematics. But although I found it easy to learn this subject, I did not feel that I wished to devote my whole life to it. Nevertheless, it was to play a beneficial role in my destiny later on, and on at least two occasions, it rescued me from death. For I would probably not have survived the eight years in camps if I had not, as a mathematician, been transferred to a so-called sharashia, where I spent four years; and later, during my exile, I was allowed to teach mathematics and physics, which helped to ease my existence and made it possible for me to write. If I had had a literary education it is quite likely that I should not have survived these ordeals but would instead have been subjected to even greater pressures. Later on, it is true, I began to get some literary education as well; this was from 1939 to 1941, during which time, along with university studies in physics and mathematics, I also studied by correspondence at the Institute of History, Philosophy and Literature in Moscow.

In 1941, a few days before the outbreak of the war, I graduated from the Department of Physics and Mathematics at Rostov University. At the beginning of the war, owing to weak health, I was detailed to serve as a driver of horsedrawn vehicles during the winter of 1941-1942. Later, because of my mathematical knowledge, I was transferred to an artillery school, from which, after a crash course, I passed out in November 1942. Immediately after this I was put in command of an artillery-position-finding company, and in this capacity, served, without a break, right in the front line until I was arrested in February 1945. This happened in East Prussia, a region which is linked with my destiny in a remarkable way. As early as 1937, as a first-year student, I chose to write a descriptive essay on “The Samsonov Disaster” of 1914 in East Prussia and studied material on this; and in 1945 I myself went to this area (at the time of writing, autumn 1970, the book August 1914 has just been completed).

I was arrested on the grounds of what the censorship had found during the years 1944-45 in my correspondence with a school friend, mainly because of certain disrespectful remarks about Stalin, although we referred to him in disguised terms. As a further basis for the “charge”, there were used the drafts of stories and reflections which had been found in my map case. These, however, were not sufficient for a “prosecution”, and in July 1945 I was “sentenced” in my absence, in accordance with a procedure then frequently applied, after a resolution by the OSO (the Special Committee of the NKVD), to eight years in a detention camp (at that time this was considered a mild sentence).

I served the first part of my sentence in several correctional work camps of mixed types (this kind of camp is described in the play, The Tenderfoot and the Tramp). In 1946, as a mathematician, I was transferred to the group of scientific research institutes of the MVD-MOB (Ministry of Internal Affairs, Ministry of State Security). I spent the middle period of my sentence in such “SPECIAL PRISONS” (The First Circle). In 1950 I was sent to the newly established “Special Camps” which were intended only for political prisoners. In such a camp in the town of Ekibastuz in Kazakhstan (One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich), I worked as a miner, a bricklayer, and a foundryman. There I contracted a tumour which was operated on, but the condition was not cured (its character was not established until later on).

One month after I had served the full term of my eight-year sentence, there came, without any new judgement and even without a “resolution from the OSO”, an administrative decision to the effect that I was not to be released but EXILED FOR LIFE to Kok-Terek (southern Kazakhstan). This measure was not directed specially against me, but was a very usual procedure at that time. I served this exile from March 1953 (on March 5th, when Stalin’s death was made public, I was allowed for the first time to go out without an escort) until June 1956. Here my cancer had developed rapidly, and at the end of 1953, I was very near death. I was unable to eat, I could not sleep and was severely affected by the poisons from the tumour. However, I was able to go to a cancer clinic at Tashkent, where, during 1954, I was cured (The Cancer Ward, Right Hand). During all the years of exile, I taught mathematics and physics in a primary school and during my hard and lonely existence I wrote prose in secret (in the camp I could only write down poetry from memory). I managed, however, to keep what I had written, and to take it with me to the European part of the country, where, in the same way, I continued, as far as the outer world was concerned, to occupy myself with teaching and, in secret, to devote myself to writing, at first in the Vladimir district (Matryona’s Farm) and afterwards in Ryazan.

During all the years until 1961, not only was I convinced that I should never see a single line of mine in print in my lifetime, but, also, I scarcely dared allow any of my close acquaintances to read anything I had written because I feared that this would become known. Finally, at the age of 42, this secret authorship began to wear me down. The most difficult thing of all to bear was that I could not get my works judged by people with literary training. In 1961, after the 22nd Congress of the U.S.S.R. Communist Party and Tvardovsky’s speech at this, I decided to emerge and to offer One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich.

Such an emergence seemed, then, to me, and not without reason, to be very risky because it might lead to the loss of my manuscripts, and to my own destruction. But, on that occasion, things turned out successfully, and after protracted efforts, A.T. Tvardovsky was able to print my novel one year later. The printing of my work was, however, stopped almost immediately and the authorities stopped both my plays and (in 1964) the novel, The First Circle, which, in 1965, was seized together with my papers from the past years. During these months it seemed to me that I had committed an unpardonable mistake by revealing my work prematurely and that because of this I should not be able to carry it to a conclusion.

It is almost always impossible to evaluate at the time events which you have already experienced, and to understand their meaning with the guidance of their effects. All the more unpredictable and surprising to us will be the course of future events.

From Nobel Lectures, Literature 1968-1980, Editor-in-Charge Tore Frängsmyr, Editor Sture Allén, World Scientific Publishing Co., Singapore, 1993. This autobiography/biography was written at the time of the award and first published in the book series Les Prix Nobel. It was later edited and republished in Nobel Lectures.

Alexandr Solzhenitsyn died on 3 August, 2008.

Copyright © The Nobel Foundation 1970

Epic badass. Okay, so my full-time job no longer seems like a good excuse for not writing every day.

What an incredible man…reminds me of Nelson Mandela.

Where the Art of War is literally War. I’m humbled and comforted today by the regret he felt over releasing his work prematurely. I’ve been there. But, a good story can resurrect itself, has its own life. I just hope I am the one to bring it to maturity and not the ones it was revealed to. I’ve read many of these books of his and as a Russian studies major, I find Russian writers write with their souls on their sleeves, a major inspiration for me.

The manuscript for Gulag Archipelago Solzhenitsyn had microfilmed and smuggled out of the country. That important precautionary act paid off when his typist was picked up by the KGB and tortured — until she revealed the location of the hidden manuscript. When she was released, she committed suicide by hanging herself…such was the War of Art under Communism!

me– just back from russia. i loved the country. i used a guide. she 38. born in st pete. grandfather literally taken away by kgb one nite. never saw him again. rest of her family (father, mom, 2 siblings and she) sent to siberia. they all survived. she learned to speak 4 languages. she became classical dancer. what kept her going was her spirit (my take of it all as i never asked her how she “made” it!). now, the russian people i met love, embrace, celebrate their new freedoms! she a joy and an inspiration. folks, love america! embrace our own freedoms. as we who served know, it aint free. i came away loving st pete/russia !!!