“The God-damned Infantry” by Ernie Pyle

Along with Bill Mauldin, Ernie Pyle was probably the most famous American war correspondent of World War II. His dispatches from the front were carried by over 300 newspapers. (Thanks to Tina McCann for sending in this piece.)

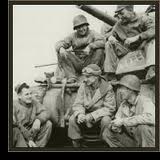

Ernie Pyle at Anzio, Italy 1944

Pyle loved the foot soldiers, the dogfaces, the grunts; he ate with them, tramped beside them under fire and won the Pulitzer Prize in 1944 for writing about them. One column of his urged that combat infantrymen be given extra “fight pay,” just as airmen got “flight pay.” Congress responded by authorizing ten dollars a month, a princely sum in those days. The law was called “The Ernie Pyle Bill.”

What I love about Ernie Pyle (and Bill Mauldin) is that they were indefatigable champions for the man on the ground. The WWII infantryman was part of a breed we don’t have any more—the citizen-soldier. Like the Greek farmer-hoplite who took down his spear and breastplate from above the fireplace and marched off to defend his city, the American citizen-soldier had no fondness for war, yearned only to get it over with and get home—but he answered the call and delivered, as Ernie Pyle did and as he describes so eloquently in the passage below.

IN THE FRONT LINES BEFORE MATEUR, NORTHERN TUNISIA, May 2, 1943

We’re now with an infantry outfit that has battled ceaselessly for four days and nights.

This northern warfare has been in the mountains. You don’t ride much anymore. It is walking and climbing and crawling country. The mountains aren’t big, but they are constant. They are largely treeless. They are easy to defend and bitter to take. But we are taking them.

The Germans lie on the back slope of every ridge, deeply dug into foxholes. In front of them the fields and pastures are hideous with thousands of hidden mines. The forward slopes are left open, untenanted, and if the Americans tried to scale these slopes they would be murdered wholesale in an inferno of machine-gun crossfire plus mortars and grenades.

Consequently we don’t do it that way. We have fallen back to the old warfare of first pulverizing the enemy with artillery, then sweeping around the ends of the hill with infantry and taking them from the sides and behind.

I’ve written before how the big guns crack and roar almost constantly throughout the day and night. They lay a screen ahead of our troops. By magnificent shooting they drop shells on the back slopes. By means of shells timed to burst in the air a few feet from the ground, they get the Germans even in their foxholes. Our troops have found that the Germans dig foxholes down and then under, trying to get cover from the shell bursts that shower death from above.

Our artillery has really been sensational. For once we have enough of something and at the right time. Officers tell me they actually have more guns than they know what to do with.

All the guns in any one sector can be centered to shoot at one spot. And when we lay the whole business on a German hill the whole slope seems to erupt. It becomes an unbelievable cauldron of fire and smoke and dirt. Veteran German soldiers say they have never been through anything like it.

Now to the infantry—the God-damned infantry, as they like to call themselves.

I love the infantry because they are the underdogs. They are the mud-rain-frost-and-wind boys. They have no comforts, and they even learn to live without the necessities. And in the end they are the guys that wars can’t be won without.

I wish you could see just one of the ineradicable pictures I have in my mind today. In this particular picture I am sitting among clumps of sword-grass on a steep and rocky hillside that we have just taken. We are looking out over a vast rolling country to the rear.

A narrow path comes like a ribbon over a hill miles away, down a long slope, across a creek, up a slope and over another hill.

All along the length of this ribbon there is now a thin line of men. For four days and nights they have fought hard, eaten little, washed none, and slept hardly at all. Their nights have been violent with attack, fright, butchery, and their days sleepless and miserable with the crash of artillery.

The men are walking. They are fifty feet apart, for dispersal. Their walk is slow, for they are dead weary, as you can tell even when looking at them from behind. Every line and sag of their bodies speaks their inhuman exhaustion.

On their shoulders and backs they carry heavy steel tripods, machine-gun barrels, leaden boxes of ammunition. Their feet seem to sink into the ground from the overload they are bearing.

They don’t slouch. It is the terrible deliberation of each step that spells out their appalling tiredness. Their faces are black and unshaven. They are young men, but the grime and whiskers and exhaustion make them look middle-aged.

In their eyes as they pass is not hatred, not excitement, not despair, not the tonic of their victory—there is just the simple expression of being here as though they had been here doing this forever, and nothing else.

The line moves on, but it never ends. All afternoon men keep coming round the hill and vanishing eventually over the horizon. It is one long tired line of antlike men.

There is an agony in your heart and you almost feel ashamed to look at them. They are just guys from Broadway and Main Street, but you wouldn’t remember them. They are too far away now. They are too tired. Their world can never be known to you, but if you could see them just once, just for an instant, you would know that no matter how hard people work back home they are not keeping pace with these infantrymen in Tunisia.

Ernie Pyle was killed by a Japanese machine gunner on Ie Shima, an island off Okinawa, on April 18, 1945—just four months before the end of the war in the Pacific.

A truly moving account. Thank you, Steven. Service – true service – is silent. It is nameless and faceless, it is anonymous. May God bless all the unsung warriors in the world today, who endure extraordinary trials and adversity so that the rest of us may have ordinary lives in peace.

First of all I have to say I love the way you write, Mr. Pressfield.

Reading this article I got myself wondering if you are “against” the professional military?

This is from about 1910:

“The Infantry, the Infantry,

with dirt behind their ears,

The Infantry, the Infantry,

can drink their weight in beers.

The cavalry and artillery

and all the the engineers,

can never beat the Infantry,

in one hundred thousand years.”

In Carlo d’ Este’s Warlord, a Churchill biography, there is not one descriptive passage as moving as this. I also like Miguel’s comment above about service. Silent, faceless, nameless. We need awareness like this injected into the daily news summaries. Wishful thinking, I know. Great content, Steven.

Ernie Pyle was a great writer, his columns represent some of the best writing to come out of that war. He told the story of the grunt better than it has ever been told.

Reminds me of a Yogi Berra quote “You can observe a lot just by watching.” Of course, watching and “understanding” or feeling what is going on is a deeper level of observation. And Ernie was definitely in touch with the dogface. Thanks Steven for insight into someone that was before my time … although not by much!

Damn, that man could write.

His column on the Death of Captain Waskow is as great an example of writing and of soldiers as you will ever see.

There is nothing I get pleasure from more compared to coming to this web-site each and every life just after work. Thanks for all of the fabulous posts!!

Sir, great article. There are, however Citizen-Soldiers still among us,as I count myself one. With a certain amount of pride I did tours of Bosnia-Herzegovina, Camp Delta GTMO Cuba, and Iraq where I was awarded a Combat Infantry Badge. I’m not a part of the Greatest Generation, yet we try. Served on missions 2.5 yrs from 9-11 till March ’06….still in, and I want another mission…..great writing Sir.