Pages from a Book Proposal

[“The Book I’ve Been Avoiding Writing” (a.k.a. “Three Years of Writing and 40+ Years of Thinking About The Lion’s Gate“) is a mini-series about the writing of my new book, The Lion’s Gate. Thanks for tuning in as it runs Mondays and Fridays over the next few weeks.]

Steve, there are three questions you have to answer in this Book Proposal [Shawn was instructing me as we were beginning the process of trying to secure a publishing deal for The Lion’s Gate]. They’re the common-sense questions that you and I would ask if we were the publisher and we were considering contracting for this book:

1. Why this subject?

2. Why now?

3. Why you?

If we can offer clear, compelling answers for these three questions, the book proposal will succeed.

I was looking forward to writing the proposal because in essence it was the same thing as what I call the Foolscap Method. “Foolscapping,” as I define it, means to write down on one page all the key elements of a book project-in-potential: hero and villain, theme, narrative device, Act One, Act Two, Act Three, crisis, climax and resolution.

Foolscapping forces you, the writer, to answer two critical questions:

What is this story about?

How does it end?

The only difference between a Foolscap and a Book Proposal would be that the first is one page long and the second is fifty-five pages long.

I made a bunch of mistakes in the book proposal for The Lion’s Gate. I made several promises, including one huge one, that I couldn’t deliver on. (More on this later.) But the section below, from the first third of the document, worked like gangbusters. It answered, at least partially, “Why this subject?”

THE CAPTURE OF THE WESTERN WALL

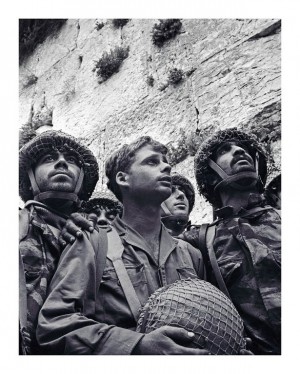

Below is photographer David Rubinger’s iconic image, taken 7 June 1967, of Israeli paratroopers in the moments immediately following the capture of the Western Wall.

This moment will be the emotional climax of our book. Everything will build to this.

What is the theme of the book? It is the reclamation (or claiming for the first time) of the soul of a people.

The story of the Six Day War is not only an Israeli story or a Jewish story. Its theme is universal. It applies not just to any people, but to any individual.

“There was one moment in the war,” wrote Yitzhak Rabin, Chief of Staff of the IDF at that time and later Prime Minister of Israel, “which symbolized the great victory. That was the moment in which the first paratroopers reached the stones of the Western Wall, feeling the emotion of the place. There never was, and never will be, another moment like it. Nobody staged that moment. Nobody planned it in advance. Nobody prepared it and nobody was prepared for it; it was as if Providence had directed the whole thing: the paratroopers weeping … over their comrades who had fallen along the way, the … tears of mourning, shouts of joy, and the singing of the national anthem of Israel, Hatikvah, ‘The Hope’.”

The soul-center of the nation is represented by the Western Wall of the temple, the holiest site of the Jewish people, from which they had been debarred by exile and Diaspora for almost two thousand years. When Israeli paratroopers captured the wall, the site was part of a forgotten alley in Jordanian-occupied East Jerusalem. Garbage lay in the gutter; the lane before the wall was only twelve feet wide. There was a rusty road sign affixed to the stones.

Of course, the theme of reclaiming one’s birthright and destiny applies to us as individuals as well. We are all in search of our spiritual center, our true core. Certainly I am. The quest has defined my life for the past forty years—as a writer, as a man, as a Jew.

That’s why I want to write this book. For myself and for others, as a metaphor for that most primal passage, the search for our Self and our center, our union with God.

Had the Western Wall been reclaimed for the people of Israel by fiat or declaration of some international body like the U.N., or by gift of the superpowers, it would not have meant nearly as much. But to be recaptured, as it was, by force of Israeli arms—that meant everything. It meant that the Jewish people were here in their ancient homeland to stay. They had taken back the holiest site of their religion and they would never again let it be taken from them.

Here’s another section from the proposal for The Lion’s Gate, a few pages later:

Tom Hanks in "Saving Private Ryan"

THE STYLE OF THE BOOK

I will write this book like a Steven Spielberg movie, meaning a global-scale story told through the actions of a small number of people, bound together by circumstance and fate, whom we will get to know personally and intimately. Those few people will serve as stand-ins for all of us and for the universality of the story’s themes and action.

Spielberg has filmed Schindler’s List, and he’s done Munich. Think of The Lion’s Gate as the third part of the trilogy—a story of the Six Day War that feels like Saving Private Ryan, only a Jewish Private Ryan.

That’s what this book is going to be, in terms of structure, cinematic feel and visceral impact.

It took me over 40 years to even find a path to finding myself. Who was I? I always assumed everybody else knew exactly who they were. Maybe they do?! I don’t know.

I’m so much happier now that I understand exactly who I am.

Of course, I thought of Spielberg’s own journey to Schindler’s List, his delays and searches.

I must quote you, now and elsewhere, because heart and soul: “The quest has defined my life for the past forty years—as a writer, as a man, as a Jew.

That’s why I want to write this book. For myself and for others, as a metaphor for that most primal passage, the search for our Self and our center, our union with God.”

Amen.

This is (one of) the blog post(s) I’ve been waiting for.

I’m not sure whether to say, “welcome to the journey, welcome home” or “thanks for providing another path, another insight, another companion, on the journey.”

So I’ll say both. And thanks ever so much.

I received my copy of “The Lion’s Gate” Friday when I returned from work. I had a busy weekend, like everyone, but found snatches throughout the days and evenings to read.

My first insights while reading were about myself. I am a bit ashamed to not have any true understanding of the fragility of the State of Israel from 1948-1967, nor the absolute gravity of the situation. 2 million versus 120 million. Pan Arabia against New Jersey. A tribe of warriors. I remember thinking that years ago when I read ‘Jews, God, and History’. There is something that touches me deeply when I read of an entire people accepting the Warrior Ethos.

I’m about 1/3 done, and I already have that familiar feeling that I want to call in sick so I can read all day–and this other quiet disturbance that soon this joy of reading will end. I will complete the book, and I don’t know when I will again be so entranced.

I agree w/ Mr Kaufmann above ‘the primal passage’, that line is powerful. As a Northern European Mutt American, I have always been a bit envious of people w/ a proud history. I remember a girl in 1st grade who was “Cherokee Indian” before PC changed our language to Native American. I was so jealous of her. We used to look for arrowheads at a park on the Columbia River in Southeastern Washington. The Indians were so cool!

While I do not share a singular-defining ethnicity, I certainly share the sentiments of ‘looking for my core’ that all people do, mutt or pure-breed.

I recently took another Meyers-Briggs test for a leadership course. I always come up as a ‘T’ (thinking) as opposed to the ‘F’ (feeling). Reading your books certainly hits upon both the T & F for me. I appreciate the humanities more and more, there are some things that can only be communicated via the arts–and that is the state of the human condition. It must be studied, pondered, and tested as much as any science to be fully human.

Thank you Steve.

bsn

Wow. That’s fantastic. I immediately understood what it was you wanted to do when you said a Jewish Private Ryan.

Has Spielberg optioned it yet?