The Western Wall, Part Two

[“The Book I’ve Been Avoiding Writing” (a.k.a. “Three Years of Writing and 40+ Years of Thinking About The Lion’s Gate“) is a mini-series about the writing of my new book, The Lion’s Gate. Thanks for tuning in as it runs Mondays and Fridays over the next few weeks.]

How does the Western Wall fit into my life? Why should I care about it?

Do I care?

I don’t know. I’m wondering, now, as Danny and I approach the great plaza.

The Western Wall Plaza today. The Dome of the Rock, third holiest site of Islam, is at left atop the Temple Mount, of which the Kotel--the Western Wall--is a retaining wall.

Above the Dung Gate, you pass through a checkpoint. Ultra-Orthodox men and women stand with their palms outstretched as you go by. Among the haredim being poor is evidence of one’s devotion to God. You must beg alms because you have given your life over to study of the Torah.

We’re through the security barrier now, walking up the slope to the Western Wall plaza. The Kotel is on the right. You can see it from a distance. It’s big. Sixty or seventy meters across and ten meters high. The stones are called ashlars. They’re huge. How the ancient Israelites wrestled them into place I have no idea.

The Western Wall is not the surviving wall of Solomon’s temple. It’s humbler than that. It’s the retaining wall that supports the elevated mount, called by Jews the Temple Mount, upon which Solomon’s temple once stood.

Titus’s legions razed the temple to the ground in 70 BCE. Why? Because the stiff-necked Jews would not accede to Roman rule. The last rebel remnant held out atop Masada, the natural fortress near the Dead Sea. When the Romans erected siege works and were within hours of overwhelming the defenses, the Jews on the summit, to the last man and woman, took their own lives.

The Romans depopulated Israel. They drove the Jews out and set them on the course of exile.

That was the start of the Diaspora. For almost two thousand years, until the founding of the modern state of Israel in 1948, the Jewish people have had no country. They have dwelt as exiles and strangers in the lands of others.

I can see the Wall clearly now. There’s a help-yourself table with kippas—yarmulkes—in case you want to put one on to approach the Wall. I do.

Around the plaza are numerous offices of religious societies and charities, built of white Jerusalem stone, rising three or four stories above the square. I check my watch. Time is about four in the afternoon. There are maybe a couple of hundred visitors, half in black Orthodox garb, half like me in civilian dress.

Six months later, when I interviewed Yoram Zamosh (who as a company commander of paratroopers was among the first Israelis to reach the Western Wall on 7 June 1967), he expressed his feelings this way:

Think about your own Vietnam War Memorial in Washington, D.C.

It’s a wall.

You stand before it. It evokes a powerful emotion, doesn’t it? I have been there myself and I was profoundly moved, though I am not an American and I have no personal connection to the losses your people suffered in Southeast Asia.

Our Wall is like that wall, except that it carries the emotion of two thousand years.

A wall is unlike any other holy site. A wall is a foundation. It is what remains when all that had once risen above it has been swept away.

A wall evokes primal emotion, particularly when it is built into the land, when the far side is not open space but the fundament of the earth itself. When one stands with worshipful purpose before the expanse of a wall, particularly one that dwarfs his person, an emotion arises that is unlike the feeling evoked by any other religious experience. How different, compared to, say, worshipping in a cathedral or within a great hall.

Danny has been to the Western Wall hundreds of times, but as I glance over to him, I see his face and posture change.

Am I feeling anything? I don’t know.

One approaches the Western Wall as an individual. No rabbi stands beside you. Set your palms against the stones. Is God present? Will the stone conduct your prayers to Him? Around you stand others of your faith; you feel their presence and the intention of their coming, but you remain yourself alone.

Are you bereft? Is your spirit impoverished? Set your brow against the stone. Feel its surface with your fingertips. Myself, I cannot come within thirty paces of the Wall without tears.

The ancient Greeks considered Delphi the epicenter of the world. This is the Wall to me. All superfluity has been stripped from this site and from ourselves.

Here the enemies of my people have devastated all that they could. What remains? This fundament alone, which they failed to raze only because it was beneath their notice. The armored legions of our enemies have passed on, leaving only this wall. In the twenty centuries since, those who hate us have defiled it and neglected it, permitted slums to be built up around it. This only makes it more precious to us.

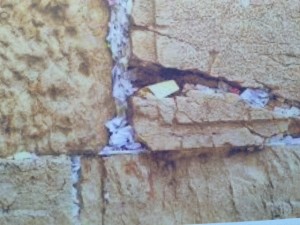

Prayers scribbled on scraps of paper are wedged traditionally between the stones of the Western Wall.

I have reached the Wall now. It’s not crowded. There’s plenty of room to approach. Danny has found a place and is praying. He’s the son of a rabbi so he knows what he’s doing.

I don’t.

I approach the wall. Between the cracks of the ashlars, the giant stones of which the wall is composed, are stuffed numerous prayers scrawled on scraps of paper. I scribble one too.

The stones are cool to the touch when you press your palms against them. These blocks have been here a long time. I’m not a religious guy. I’m an American. I have no real background in Judaism. I’m a bad Jew. But, pressing my forehead to the stones of the Wall, I feel something in my knees.

Zamosh said the experience is solitary. It is. For me it evokes no verses of scripture or even coherent thoughts. No quotable insights come. I don’t experience a flash that changes my life. But when I turn away from the Wall and cross to Danny to walk back up the slope, I find myself putting my arm around his shoulder.

“You okay?” he asks.

“Yeah. Fine.”

Danny has lived in Israel for more than thirty years. He has probably been to the Wall five hundred times. Still I see something in his eyes. That same something is in my eyes too.

“Wanna go get something to eat?”

He puts his arm around me too.

“Yeah,” I say. “That sounds good.”

Very emotional-provoking. I am reading the Book Thief presently – similar feelings of dealing with history in an emotional way. A wall has no heartbeat, yet, it evokes powerful emotion. Just the names of the death camps from WWII bring out emotion. Thanks Steve.

If I remember correctly, the Western Wall was part of Herod’s expansion project, begun around 19 BCE. After the First Temple (which Solomon built) was destroyed by the Babylonians, those who returned after 70 years – in the Persian period – rebuilt the structure, but it was not on the scale or of the quality of what Solomon built. Herod renovated and expanded the already existing Second Temple. Part of that renovation was building the Wall.

Also, I’ve never hear that “Among the haredim being poor is evidence of one’s devotion to God.” One doesn’t get rich if studying Torah is one’s life occupation, but there’s no mitzvah in being poor, either. (As far as I know.)

I remember my first experience at the Wall. I was overwhelmed more by the people than the Wall itself. I was rather numb. The second time I went, the next day, I had the more “expected” emotions.

I disagree: I think you did know what you were doing, because what you did came from your soul. Being “religious” (or “spiritual,” if you prefer) begins from within.

Steve, you are not a bad Jew. You can’t be.

I have to agree with David – you are not a bad Jew; a bad Jew could not have had this moving experience.

I don’t know how it is on the men’s section of the prayer area at the Kotel (Western Wall), but on the women’s side most of the beggars are not asking for money for themselves. They ask “for the poor brides of Jerusalem,” “for a poor widow with 8 children,” “for a young man who needs heart surgery.”

On my first visit to the Kotel 30 years ago, the thought of all the generations who wanted to pray here but could not do so brought tears to my eyes. After over a hundred visits to the Kotel, that thought still does so.

Walls are built upon foundations. Walls built upon ignorance and fear keep out the light of truth. There are no places or days holier than others. A space or time is comprised of the holiness one ascribes to it. Everyday is my birthday and independence day. Every place and thing is holy. We are all holy. We all are coming to this realization.

God is good. Through continuing revelation we attain God’s likeness. We all reap the fruits of our desires whether they manifest in the physical or not. We all through the consequences of folly will come to know that when our desire is to know and be as God, all things good will follow. This is the wisdom revealed to Abraham and all others who seek God with all their hearts. http://www.kabbalah.info/files/public/Files/ebooks/The_Secrets_of_the_Eternal_Book.pdf

Blessed be.

I don’t cry at movies but I’m crying at your testimony.

Shabbat Shalom.

Whoo ….. I had tears just reading your account on this Steven. I am religious and I am very curious where all this is taking you spiritually. I am 76 yrs old and like my wife likes to say, “honey, I’ve been around”. Personally I am betting the farm on the God of Abraham, Isaac and Jacob plus the Prophets. I know this site has to do with creativity, writing, art,etc. but for me this IS the conversation. I am very interested in watching what you are becoming. My prayers are with you.

God Bless – Bing

This is a space that raises Terror in the heart of The Resistance, for it is the home ground of “The Assistance”.

Today’s blog is exactly why I return. The product, “The Lion’s Gate”, is so sweet–but seeing behind the veil is even better. One of these days I may post an email I sent after we lost one of our troops in Afghanistan. It was pretty raw, but cathartic. I did not know that I needed to write it, but afterwards I felt better.

I do not know if the blog is cathartic for you Steve, but I know it is very important for us to read and understand. Brene Brown likes to use the word ‘vulnerability’. I prefer ‘exposed’, doesn’t sound so feminine…sorry ladies…but your exposure is very instructive and permisive.

bsn

I moderated our book club on Wednesday. We discussed Night by Elie Wiesel. Seven years ago, I sent Mr. Pressfield the photograph known as “The Last Jew in Vinnitsa” and said, ‘You need to write about this.’ He responded, “I think you should.” Three years later, I published The Hamsa. We are on sacred ground

What I love about this post is how the sacred exists because of the meaning we bring to it. And what I feel is more interesting is how after profound experiences mundane aspect of life, life grabbing a bite to eat, insert themselves.

I just watched your book discussion on CSpan’s Booknotes at the Diesel Bookstore in Santa Monica.

I have not read your books before, but was fascinated with the intelligent discussion and the questions that were asked and answered. I have been to Israel many times, not made aliyah, but like you, my heart remains there.

I shall shortly order “The Lion’s Gate” for myself and also for my husband to read and then shall read the rest of your books.

I am delighted to have heard you and found a new “favorite author.” Keep on writing, because I fully intend to keep on reading.