How to Write a War Memoir (or any memoir)

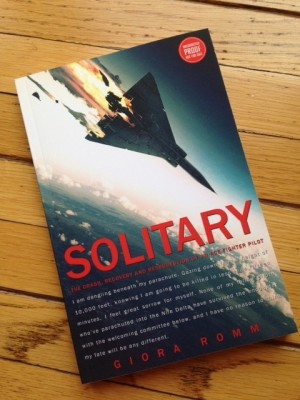

I am dangling beneath my parachute. Gazing down from a height of 10,000 feet, knowing I am going to be killed in less than fifteen minutes, I feel great sorrow for myself. None of my fellow pilots who’ve parachuted into the Nile Delta has survived the encounter with the welcoming committee below, and I have no reason to think my fate will be any different.

"Solitary" by Giora Romm

This is the first paragraph of the true-life memoir of Israeli fighter ace Giora Romm, titled Solitary, which was a best-seller in its original Hebrew under the title Tulip Four, Romm’s aircraft’s call-sign on the day he was shot down.

How do you write a war memoir (or any kind of true story)?

Tens of thousands of such tales have been published and no doubt thousands more are in the works right now. Veterans of Vietnam and Desert Storm, of OIF and Afghanistan have sought in countless manuscripts to tell their stories, to recount what they’ve done and witnessed and felt.

What makes a memoir work? Why do we read one and put another aside?

When you get down to about 2,000 feet, you can feel the ground approaching, and the rate of descent seems to accelerate with each passing second. The last part happens very fast. From about 100 feet above I can see that I am going to hit near a group of black-clad women who are shrieking in horror and trying to scramble out of the way. And then I hit the ground.

Within seconds, the first Egyptian villager is standing over me. Min inta? “Who are you?” he asks with much excitement. I ponder what answer will make him refrain from killing me—no easy task to gauge by the look on his face. The tumult escalates as more villagers press in towards me, shoving and yelling and trying to talk to me.

Who am I, then, at this moment?

The opening paragraphs of Giora Romm’s Solitary grip you. They suck you in.

But if you read them closely you’ll see that the deeper theme—the dimension that will elevate this narrative beyond “true war story” or “prisoner-of-war tale”—is already present.

Who am I?

Writers think in metaphors. To every event/character/narrative, they ask, “What does this stand for?”

Giora Romm was taken prisoner by his nation’s most bitter enemies; he endured a terrible ordeal; he was released; he returned to duty to command a fighter squadron. He led men into battle over the same enemy territory where he had been shot down, imprisoned, and tortured.

What does that mean?

What is it a metaphor for?

It is not enough, if you’re a warrior, to simply tell your story of war. The reader has read a thousand war stories. Nor does truth count. You get no points for “This really happened.” The warrior’s experiences, if their recounting is to hit home with the reader, must be evaluated on the same terms as fiction, meaning their narrative power and soul-relevance alone.

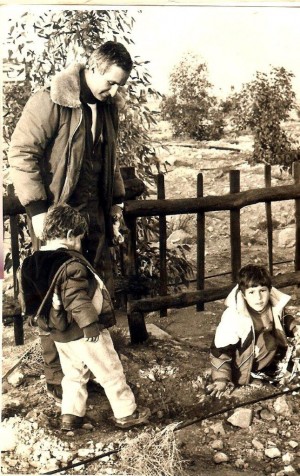

Giora Romm in 1983 with sons Assaf and Yuval

The Birdman of Alcatraz is a true story of imprisonment, as Giora Romm’s was. But Birdman can’t just be about a guy in a cell with a canary. It has to be about imprisonment as a metaphor. The fact of captivity must be addressed not only on the “action” level (where it would produce scenes of confrontation, brutality, etc.) but on the deepest emotional, psychological and spiritual planes.

The Birdman Robert Stroud’s literal captivity is experienced by us as a metaphor for whatever forces “imprison” us in our own lives. And his triumph via the humblest, most random happenstance—his nursing back to health of a wounded sparrow that had landed on the ledge of his cell window—resonates in our hearts as a path out of our own self-incarceration.

Giora Romm asked himself, What is my story about?

When I met him in Israel in 2013, I asked him what his process had been. Giora is not a professional writer and doesn’t claim to be. He simply understood on instinct.

Is my story about imprisonment, Giora asked himself.

Is that the metaphor?

No, he decides.

Because the most important part of the journey happens after he’s released.

Flying again. Taking command of a squadron. Leading men into combat over the same part of the Nile delta where he was shot down before.

That was the real hell. That was the adversity in which he was even more alone than he had been in solitary confinement. That was the ordeal that impelled him to call upon his deepest interior resources.

The metaphor, Giora decides as a writer, is the inner war.

The story, he concludes, is about resurrection. Self-resurrection. Alone. Solitary. A shattering fall from a great height succeeded by a climb back through hell to reach, in an altered and entirely new form, not the place where he had once been but another station, unlike any he had experienced before.

This is how a writer thinks. It’s how Giora thought. It’s how a war memoirist (or any memoirist) must think, if he wants his story to succeed on levels beyond the superficial.

I asked Giora once, “How did you know to think that way, to write that way? Did somebody teach you?”

He laughed. “I just knew,” Giora said, “that I didn’t want to write one of those books that progressed through, ‘Then I did this, then I did that.’ I would have bored myself to death if I had written it that way.”

Sounds a lot like Joseph Campbell’s hero’s journey.

I agree with TJ – this is the hero’s journey, whether it is memoir or fiction. Its universal appeal is that we are all fighting an inner war of one kind or another and each of us strives to be the hero of our own journey. I just finished reading a novel a few days ago (“Never Change” by Elizabeth Berg). The inner war here takes place as one of the characters, a man with a terminal brain tumor, reaches a decision about his destiny and, in this reader’s opinion, achieves hero status. This book left me wanting to live a better life and to be a better writer. I’ll wager Romm’s memoir does the same thing.

The emergent field of narrative non-fiction conforms to your rule that they “must be evaluated on the same terms as fiction, for their narrative power and soul-relevance.”

I suspect we are just beginning to understand the power and pervasiveness of metaphor. Instinctively, we respond and appreciate from infancy, as metaphor is wired into our synapses.

Solitary is next up on my reading list.

Thanks.

Interesting book recommendation too.

I am always amazed how a story can go this deep and the word God is never mentioned. Even the word resurrection was used. When I was 22 yrs old I was swimming off Santa Monica beach, CA and swam out to far. Swimming back I became hysterically exhausted. I was just ready to drown when a voice came out of my mouth that said ‘ GOD HELP ME’. A force out of nowhere threw me on my back and I was able to float enough to regain enough strength to get back. I am now 76 yrs old and that same voice still comes out of my mouth often. Another form of the Hero’s journey I guess.

Thanks

I just love this site. I’m moved by Steven’s writing, then again by all the posts. Thank you Steve, and thank you that add fuel to the insight.

bsn

I just finished one of those war memoirs that is put aside, completely ignored, never validated by the best seller lists. It’s a prisoner of war story of 100 pages, published in 1989. The publisher is long gone. The narrative is clunky, poorly written, with not much or no help from editors. I got the book with the writer’s own handwritten dedication on front to the Central State University library. It’s a forgotten book, by a forgotten African-American soldier, in a forgotten war(Korea). But some of the passages in James Thompson’s True Colors: 1004 Days as a Prisoner of War are incredible. There are many extraordinary stories that deserve resurrection.

That’s the thing about memoirs, or personal essays–the most important parts happen after, in the looking back, recounting, piecing together, allowing for, maybe even the letting go. When we share it it must have been “for a reason?” That’s why I’ve decided to write what I was avoiding, too. My mom died this year. I’m writing letters to her now, on Medium. It’s too late of course, to say everything. Or is it? I don’t know what else to do about it. Except not do it, and that doesn’t seem right either. So yeah, resistance.

I keep thinking it’s her journey I’m addressing, but it’s really feeling like mine as I get writing, and then, it hits me. It’s all of ours. We all are going in the same direction, and we all know people who died, or will. We all will want to have, or should have, said more before they died or before we die. What if everyone told the truth? 🙂 Fine. I’m writing the letters. Even though my mom is dead already. They stand for not waiting. They stand for inevitability. They stand for love and eternity. PS Thank You Steven

Thank you Mr Pressfield for being a crystal clear voice, and a light shining through every fog

Solitary is a great read, for the self-resurrection Steve mentioned as well as the revelation of the human spirit during Mr. Romm’s captivity. He shares moments between himself and his captors that many fiction writers would dismiss because they seem too outlandish or too mundane, but they are precisely what connected me to a situation I will never experience.