Dudeology #2: Combining Genres

We were talking last week about The Big Lebowski being a film in the Private Eye genre. But what really makes Lebowski so inventive and so interesting is it’s a mixed genre. It’s a Slacker/Stoner tale (like Dazed and Confused, Go, Clerks, or any Cheech and Chong movie) conceived, structured, and executed as a Detective Story.

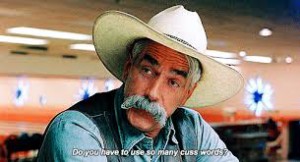

Sam Elliott in The Big Lebowski. “Now this feller, the Dude … I think he figgered out something new.”

What does this mean for you and me as writers?

It means that mixing genres is one of the most canny and fun tricks we can pull to come up with something new and fresh and exciting.

Mix the Private Detective genre with Sci-Fi and you get Blade Runner.

Combine it with a Geezer Pic and you get The Late Show, starring Art Carney and Lily Tomlin.

Blend it with historical fiction and you get The Name of the Rose.

But let’s dig a little deeper into The Big Lebowski. The concept of the film is this:

Let’s tell a story that hits all the beats [conventions] of a Sam Spade/Philip Marlowe Private Eye Story, but instead of having a hard-bitten detective as the hero we’ll have a sweet, lovable stoner.

How does that pay off for the writers, Joel and Ethan Coen? It pays off because this simple creative twist—stoner instead of film-noir private eye—makes every character and line of dialogue feel original and inventive. Each scene gives the filmmakers an angle to make a fresh point about America, about popular culture, about how things have changed in the past generation or two.

Consider this comparison:

Here’s Jack Nicholson as Jake Gittes in an obligatory moment from Chinatown—the scene we see in every Detective Story, where the private eye defends his actions against the dissatisfaction of his employer (in this case Faye Dunaway as Evelyn Mulwray).

“I like my nose. I like breathing through it.”

JAKE GITTES

Okay, go home. But in case you’re interested your husband was murdered. Somebody’s dumping tons of water out of the city reservoirs when we’re supposedly in the middle of a drought. He found out, and he was killed. There’s a waterlogged drunk in the morgue—involuntary manslaughter if anybody wants to take the trouble which they don’t. It looks like half the city is trying to cover it all up, which is fine with me. But, Mrs. Mulwray … I goddam near lost my nose! And I like it. I like breathing through it. And I still think you’re hiding something.

That’s old-school hard-boiled Private Eye lingo. Now here’s the Dude from The Big Lebowski hitting the same beat in the back seat of a stretch limo, confronted by his pissed-off employer, the actual “Big Lebowski”:

DUDE

Look, man, I’ve got certain information … uh … certain things have come to light. Uh … has it ever occurred to you, man, that instead of running around … uh … blaming me. It could be … uh, uh, uh … a lot more complex. It might not be such a … uh … simple … you know? I’ve got information, man. New shit has come to light!

” … information has come to light, man!”

Chinatown was set in 1937 (although it was actually made in 1974.) Lebowski is basically present-day, though it was released in 1998.

Has America changed in those fifty years? Are people different? Have styles-of-being evolved? I daresay we’d have to search long and hard to find a better (or more hysterical) side-by-side comparison than that depicted in these two scenes.

That’s the payoff for us writers when we combine genres. Everything old becomes new. Everything familiar becomes fresh.

Mixing genres works in all fields and almost always produces something interesting. Blend a sports car with a muscle car and you get a Corvette. Mix the same vehicle with a luxury sedan and you get a Porsche Panamera. Combine a panel truck with a car and you get a minivan.

It works just as well with swimsuits and salads and popular music.

Think about using this for your own stuff.

Genre A + Genre Z = New Genre AZ.

Great timing on the genre pieces — this week I’m discussing that very element of screenwriting in my Summer Script Analysis class and both “Dudeology” posts will be mandatory reading.

Thanks again!

You just turned my rudder out of the windless still waters of a memoir into the breeze and rolling waves of non fiction novel. I hope the muse has arrived. Thanks

Great side-by-side comparison indeed – thanks!

Just be dead sure, when you do this, to know which genre will predominate, which genres conventions to follow. I keep writing [other-genre]-mysteries, but putting the mystery on top instead of underneath.

I alluded to this in my response to the last post. AS both you and Joel Canfield note, one genre will dominate. Perhaps this is why Science Fiction is now so popular (wasn’t always – thank Star Trek, 2001: A Space Odyssey and of course Star Wars) and has always been so flexible. In conversation with Harlan Ellison, Isaac Asimov remarked he was prepared to accept a rather broad definition of the field. There SF Mysteries (Asimov’s Lije Bailey novels, and several short stories), SF Westerns (perhaps Star Wars, definitely Firefly), SF Romances (too numerous to name), etc.

Mixed genres probably need conventions from both genre, although again, one will dominate. Nor is it just a matter of setting. That is, an SF Romance can be just a romance set in outer space or whatever. In that case, the SF part may not be a genre of the story so much as the setting or background. To be a true mixed genre story, the story must partake of both. Thus, for example, an SF Romance will follow Romance conventions (boy meets girl, boy loses girl, boy gets girl – or a variation) as well as SF conventions, mainly by asking what if questions. What if gender was fluid (i.e., sometimes male, sometimes female)? (See LeGuin’s Left Hand of Darkness which, while far from a romance, yet considers and plays with romance genre conventions). What if there is more than one sex (that is, male-ish, female-ish, and else-ish)? (Asimov plays with this concept in his The Gods Themselves.)

To go back to Steve’s example, “The Big Lebowski” is a detective story, but the setting and protagonist are from a Stoner story.

Of course, one can write in only one, or a standard, genre. But even then, there are sub-genres (as in Shawn’s chart) which have their own requirements or variations on the genre conventions.

OK, I am getting educated but I’m also getting confused. I’ve been picturing a genre as a sign hanging over shelves in a bookstore. I know my book has to be easily categorized for the store to order it and shelve it. True? So, combo genres still have to fit on an existing shelf, which is why one must prevail. Yes?

Mia, that’s why we’ll sometimes find the same movie (or book) in two or more different sections of the store. And why us story nerds will be getting into fist fights over which place is correct.

Shawn Coyne also discusses the difference between commercial genre, the sign in the store, and literary genre, the signs we writers follow. Much crossover, but many differences.

I laughed out loud after reading The Dude’s quote. Absolutely hilarious. Great post!

Another example is Eric Ambler using the 1930s detective genre to mix and create the thriller genre with his classic novel A Coffin for Dimitrios. A college lecturer and writer of detective novels tries to explain the strange life and death of this man Dimitrios, one of those “unhappy men who are confounded by the difference between the stupid vulgarities of real life and the ideal existence of the imagination.” All of Ambler’s novels are still fresh today.