Truth, Truth, Truth, Fiction

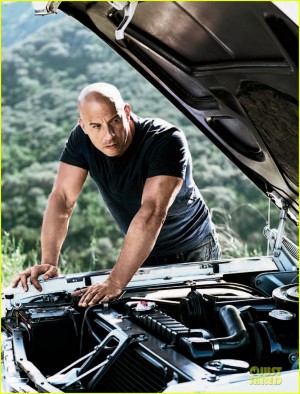

Almost any story, if it’s gonna have real power in the climax, needs a blockbuster bang or invention—something that nobody’s seen before or, if they have seen it, something they’ve never seen done in this unique way. Often this bang is contrived and pushes the bounds of believability. Can a sperm whale really ram and sink a whaling ship? Can Vin Diesel really leap a car out of one skyscraper, soar across 100 feet of empty space, and land safely inside another skyscraper? (And, by the way, is his name really Vin Diesel?)

We want to believe, Vin!

The tricky part about achieving this kind of Big Bang is that the moment inevitably strains, and possibly overstrains, the reader’s willing suspension of disbelief. The last thing we want as writers is for our readers to think, “Gimme a break! That B.S. could never happen!”

The solution is in the set-up. In no few books and movies, the main freight of the story—beginning, middle, and part of the end—is about nothing except preparing the ground for that one Power Fiction at the end. Ninety percent of the tale is dedicated to creating a world in which such a Big Fiction could plausibly happen. Have you seen Murmur of the Heart by Louis Malle? The whole movie is a buildup to the climactic scene of a 14-year-old-boy having sex with his Mom. And it works.

How do we achieve that?

The answer is truth, truth, truth, fiction.

When I say truth, I mean plausible scenes and believable characters. They don’t have to be literally true in the real physical world. But they must be scenes and people and concepts that, within the universe of the book or the movie, appear believably realistic. Can a penniless WWI vet really reinvent himself as “Jay Gatsby” and evolve in just a few years into a dashing zillionaire who builds a mansion that becomes the epicenter of the Roaring Twenties social scene in New York? He can if the story is told from Page One by Gatsby’s friend Nick Carraway, who tells us truth, truth, truth—plausible scene after plausible scene of his own life and of the world of the 20s—until, when he introduces Gatsby, we don’t even realize how far the envelope of believability has been pushed. We buy in. We believe.

Indeed, we have no problem with dragons on Game of Thrones because a universe has been created by the writers in which such creatures can plausibly exist and even interact with humans.

As beginning writers, we’re often counseled to conduct rigorous research, to pay scrupulous attention to detail. And we should. Don’t call it a tree, name it a loblolly pine. Make sure that that ’40 Oldsmobile has a Hydra-matic transmission. The reason these details are so important is because they, employed as elements in a sequence of other true facts, constitute the “truth, truth, truth,” whose role is to set up the Big Fiction.

Salesmen say. “Get the customer saying yes to the little things. Then he’ll say yes when we ask, ‘Are you ready to buy?'”

You, the writer, are a salesmen too. You’re selling your story. Remember, we your readers want to believe you. We want dragons to talk. We want Rocky to go the distance with Apollo Creed. Your job, Ms. Writer, is to seduce us. Your task, Mr. Tambourine Man, is take us on a trip aboard your magic swirling ship.

If you’re describing a dinner at The Palm whose climax will be one character pulling out a .45 and blowing another character’s brains out (i.e., something that has never happened in real life), we your readers need you to set it up by telling us all the details of the tablecloth, the soup course, etc. And we need everything to adhere to the conventions you’ve established for your story, to be consistent with what came before. The way the characters talk, the clothes they wear, what the emotional dynamics are between them. Keep it all of a piece with no inconsistencies. So that when, in the seventh course, one of your diners whips out an automatic and pumps six rounds into his rival’s chest, we your readers will say, “Oh, that makes sense.” Because the characters stayed true to the ground rules you had set up for them. And because they used the right spoons during the soup course.

Truth, truth, truth, fiction.

It works.

Thnx! Great advice…. dragons flying in our world would be nonsense, but in an created universe everything can happen. Create a world of truth; even if it’s untrue…

“Truth, truth, truth, fiction” – this is worthy of posting above my computer. I never thought of a writer being a salesman before, but you make a good case for it – thanks for a great post!

As a writer who splits herself between fiction and content marketing, this rings so very true.

It’s about world building whether it’s in the creation of a virtual fireside on your website, a post apocalyptic future, or a semi-autobiographical novel.

Thanks for this.

…curiously (or maybe not) it’s also the blue print for many image based healing techniques…

Great post!

I agree…Gatsby would have been a different animal were it not for Nick.

By the way San Andreas didn’t do what you describe above very well!

I guess I’m an atypical reader. It drives me crazy to read a scene that goes into infinite detail. To start reading which correct soup spoon was used or what the table cloth looked like or what meals were served including garnishes immediately causes me to start skimming the story. Having details in a story is important, but at what point does it go overboard? Reading that a character is wearing a suit, even a pin-striped suit is one thing. Reading about the suit color, fabric, thread count, and designer…I’m flipping pages to move on and skip the blather.

Mmmm…not the point, Cheryl. (Hulloo, Cheryl!)

Not excessive detail, but enough detail.

Your books take place in a fantasy world. You’ve set up a couple things that make no logical sense, but which you use to advantage in your story: the mental powers being different from person to person, and the fact that in certain well-defined circumstances, they don’t work.

That’s detail we need. If you spring it on us in situ (“and then she failed because her powers didn’t seem to work in this particular location”) you just lost us. You don’t do that.

Remember, the writer’s definition of truth isn’t the absolute definition. It’s “whatever makes the story feel real to my reader.”

Put them in a real place, with real stuff, as it makes sense to your story. Lay the groundwork for the Big Leap.

And then, when you make the Big Leap, we make it with you because hey, it makes perfect sense based on the truths you’ve set forth thus far.

Right?

Gotcha, Joel! 🙂

I do agree with you there. I guess it’s that mysterious line of enough crossing into too much. How and where do you gauge that?

If the detail directly pertains to the story, or will become important later, it needs to stay.

If it has zero to do with the story, I’m inclined to leave it out of my work and also want it left out of a story I’m reading.

Cheryl, I have read plenty of novels that include too much detail and I’m sure you have too. There is a line of too much detail that writers cross for some readers (and they will skim over those parts of the novel) but other readers will think the attention to detail is perfect.

True, of course.

But what does “pertains to the story” mean?

“Critical to plot points” is not the only definition. What about “shows something about the characters” or “amplifies the reader’s vicarious experience” ?

All the talk about Fritz’s cooking has nothing nothing nothing to do with the plot in a Nero Wolfe novel. But Rex Stout knew his audience, and that we’d revel in Wolfe’s debates with Fritz about whether to add the butter now, or later, and in Archie’s silent agreement with one or the other of them but keeping quiet because he’s smart. And hungry.

What a wonderful way to phrase the “it’s all in the details” or the need for verisimilitude in storytelling. It’s all a set-up for the climax. Doesn’t this also tie into genre, because the kinds of detail needed depend on the story’s genre, right? It might be most obvious in science fiction and fantasy, but even realistic or literary fiction calls for a different sort of detail – truth – than a mystery, which is also has a realistic setting. So wouldn’t genre help dictate the truth, truth, truth part of the story, just as it helps define the fiction, and whether it works, at the end?

World building is critical everywhere. 🙂