The Dude Abides … but in What Genre?

[Reminder: only two more days to order your free e-version of my new book on writing, Nobody Wants To Read Your Sh*t. Offer expires at midnight, June 30. Click here to download. Totally free. No opt-in required. Takes 38 seconds or less.]

I was talking three weeks ago about the preparatory files I use before plunging in on a first draft. The first file is one I call Foolscap. Here’s the first question I ask myself in that file:

“What’s the genre?”

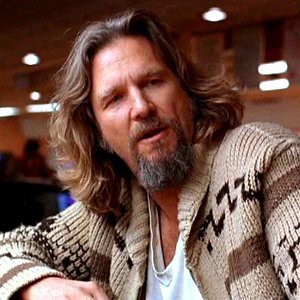

The Dude doing his Philip Marlowe thing

I’m asking, “What kind of book am I writing? Is it a Western? A Love Story? What exactly is the genre of this idea I’m working on?”

I ask this first because it’s the most critical question a writer can ask. And because, once I answer it, I’m halfway home.

At this stage (before the first word of a first draft) I may have only the vaguest notion of what my story is. Maybe I’ve got one character, a few scenes, maybe less than that. I’m groping. I’m like the blind man trying to figure out if he’s working with an elephant.

So I ask first, “What’s the genre?”

Why do I ask this? Because genres have conventions. As soon as I identify the kind of story I’m telling, I automatically have a road map, a blueprint for its shape, its trajectory, and its content.

Consider The Big Lebowski by Joel and Ethan Coen.

I have no idea how the brothers evolved their story but I’ll bet anything they started with “the Dude.” They probably even had Jeff Bridges in mind. My guess is they knew the tone of the movie; they knew it would be zany, wry, deadpan. And they knew the feeling of the scenes they wanted. But I’ll bet that, at first, they weren’t sure exactly what genre, what kind of movie it was. Then …

“OMG, it’s a Private Eye Story! It’s a Detective Movie but instead of a having a hard-bitten Sam Spade/Philip Marlowe type as our hero, we’ll have a lovable, slightly-dim stoner.”

Identifying the genre was the stroke that split the diamond. At one blow, the Coen brothers could see the whole movie.

Why? Again, because genres have conventions. A Private Eye Story has obligatory scenes. Every movie or novel in this genre makes stops at these mandatory stations. The audience would be furious if it didn’t.

Next step for the brothers? Cue up Chinatown, The Maltese Falcon, Farewell My Lovely. Watch them or read them with this thought in mind: “What can we steal? What happens to Jack Nicholson, to Bogie, to Robert Mitchum? Whatever that is, we’ll make it happen to the Dude.”

See what I mean about genre?

Once we know what type of story we’re telling, we’ve got half the struggle licked.

But back to Private Eye Stories. What scenes can we count on? What scenes will be in every tale of a gumshoe-for-hire?

- He’ll be approached (usually by a rich person) to take on a case.

- Halfway through the story, he’ll be hired by another individual (usually intimately connected to the first rich person) to take on an additional case. Both assignments will involve “finding” somebody or some thing.

- The hero will become romantically involved with a beautiful woman, usually his client. This liaison will not go well for the hero.

- For sure, our detective will get beaten up. Usually more than once.

PHILIP MARLOWE

Moose’s skillet-sized fist hit me. A pool of inky blackness

opened at my feet and I tumbled into it …

- Our hero will have a sidekick or partner, possibly a Peter Lorre-type. This cohort will inevitably get our hero into trouble.

- There will be scenes of betrayal, duplicity and mistaken identity.

- There will be red herrings and multiple plot twists.

- In the end, our hero will actually solve the crime. He and no one else. He will come out on top but, alas, without the girl (and perhaps without his fee, his business, or his sanity.)

The Coen brothers knew these conventions. They understood that these were the sinew and marrow of the Detective Story genre.

So the Dude gets hired by the Rich Guy (the actual “Big Lebowski”), then hired again by his daughter Maude, played by Julianne Moore, who indeed will seduce him for her own nefarious purposes. Beat-ups? The Dude will get pummeled by goons, attacked in his bathtub by nihilists, have his White Russian drugged by Ben Gazzara, the porn gangster. His buddy John Goodman will get him into all kinds of trouble. Together they will chase down numerous red herrings, but, in the end, it will be the Dude and only the Dude who cracks the case.

DUDE

She kidnapped herself, man!

My favorite scene in The Big Lebowski is, sure enough, a genre-specific convention: the moment when the hero, in bed with the Beautiful Client, reveals his own (surprisingly profound and emphatically on-theme) backstory. Remember that moment in Chinatown? Jack Nicholson as Jake Gittes is lying back on the pillow, having just made love to Faye Dunaway as Evelyn Mulwray. She asks him how he got into the private detective racket and he tells her he used to “work for the District Attorney” (meaning he was a cop) in L.A.’s Chinatown.

JAKE GITTES

You can’t always tell what’s going on there. I thought

I was keeping someone from being hurt and actually I

ended up making sure they were hurt.

That scene, for sure, was front-of-mind for Joel and Ethan Coen when they put Jeff Bridges in the post-coital sack with Julianne Moore.

MAUDE

Tell me about yourself, Jeffrey.

DUDE

Not much to tell.

(tokes on a joint)

I was one of the authors of

the Port Huron Statement. The original … not the

compromised second draft. Did you hear of the Seattle Seven?

That was me … uh … Music business briefly … roadie for

Metallica. Speed of Sound tour. Bunch of assholes …

Genre conventions are not “formula.” They’re opportunities for tremendous creativity and fun and depth, as the Coen brothers proved in this and a bunch of other movies.

Before you write a word of your first draft, figure out what genre you’re working in. Then bone up on the conventions of that genre and take it from there.

Genre conventions – foundational building blocks for story – thanks for driving this lesson home again!

Absolutely love the new+free ebook. Thank you, Steven. Easy read, and, as always, extremely insightful. It is another winner for you and your team. I’ll keep spreading the word on the great work all of you are doing. Cheers! -Rock

Oh man, I have struggled with genre bending throughout my writing career. My first novel, I was told, was “too grown up” for a middle grade (big words and long, complex characters). The one I am writing now is a buddy comedy though people keep thinking its going to be horror. Gad!

Would be awesome to see a list of genres available. Ha ha. Save The Cat has some, but his genres aren’t the same. While some might say Western, he might call it buddy comedy. Others might say horror where he would say “Monster in the House.”

This is really good advice!

PS – I loved your new book. Thanks for giving it out. But please also provide me a way to be able to pay you because I want to. 🙂 Is it on Amazon?

Aww…nevermind. Found the big link up top and ordered myself a hard copy. Many thanks 🙂 Cover is hilarious, by the way.

Erika, have you seen Shawn’s genre 5-leaf clover at Story Grid?

http://www.storygrid.com/resources/five-leaf-genre-clover-infographic/

I know of no more complete list.

I never realized how important knowing your genre is when developing a story line. I did’t know the rules for the genre of my story, so the plot didn’t flow. I figured it out in the end, but I took the long way around.

Thanks for the great tips!

So I clicked on the link for three weeks ago, “Just Write the damn thing?” Part One. But I can’t find part two. checked the archives. Tried the search function. Help?

Thanks.

Why is it so hard to figure out my genre? It’s right up there with deciding what to be when I grow up… rabbi or barrel racer, can’t decide which… This post inspires me to try out different genres in my mind, like different life paths. What a great idea! I’ve been so busy trying to find “the one,” I forgot to simply experiment mentally, as you and Shawn talked about on the podcast for choosing point of view. Thanks!

The genre conventions are super helpful. Genre is still a dirty word with some people. Possibly a hangover from hi-lit snobbery?

Anyway, when are you going to do face to face workshops? I’d get on a plane from Australia for that.

Thanks heaps.

The two most important concepts I have gotten from Mr Pressfield are The Resistance, and the critical importance of finding the genre. I am at beginning of a project right now, and looking at genre opened up a different way of thinking about the piece. Important stuff!

Thank you, thank you, thank you.

Separating literature into “literary fiction” and “genre fiction” may work for publisher’s marketing efforts, and in English Literature departments it used to be a way to dismiss much contemporary work. Standard genre fare was studied if it had stood the test of time. Often, the poorly written stuff from a particular period was studied not for its inherent worth, but for what it said about the culture of the time, and the conventions and expectations that the great works were nurtured in and against which they often pushed. The rise of the pulps made it easier to dismiss the genres, because the characters were so flat, and so many plots, and so much of the dialogue, was cliched. But yesterday’s potboiler often became today’s classic.

Pride and Prejudice, one of the finest novels ever written, is a romance. But it’s not taught that way, unless one is teaching a course on the history of the romance genre. So is Wuthering Heights, for that matter. Dickens wrote detective stories, and Wilkie Collins’s The Moonstone is still studied with other Victorian literature.

So literary fiction probably fits into one of the standard genres, coming-of-age (bildungsroman), for example. Nor is the contemporary setting a requirement. The Help is set in the early 60s, and a lot of good genre fiction is set in the modern world.

Still, we have to be aware that genres are fluid. War and Peace, considered the greatest novel ever written – is it a war novel, a love novel, a historical novel? What is its major genre, of which the others are sub-genres? Huckleberry Finn, considered the greatest American novel, is squarely in the tradition – genre – of the picaresque satire (Gulliver’s Travels, Humphrey Clinker), yet relies heavily on the Western Tall Tale, with which Twain was very familiar.

How many sub-genres of Science Fiction, or Fantasy, are there? Within the detective/mystery genre there’s cozy, noir, hard-boiled, etc. When deciding which genre within which to write, do we initially have to settle on the sub-genre, or will that emerge when we have a handle on the genre?