Write It Like a Movie

The men were silent and they did not move often. And the women came out of the houses to stand beside the men—to feel whether this time the men would break … The children stood nearby, drawing figures in the dust with bare toes … Horses came to the watering troughs and nuzzled the water to clear the surface dust. After a while the faces of the watching men lost their bemused perplexity and became hard and angry and resistant. Then the women knew that they were safe and that there was no break.

Feel the power in this passage from John Steinbeck’s The Grapes of Wrath?

John Steinbeck was awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1962

Why does this simple passage work so well?

I think it’s because it’s written like a movie.

The characters’ feelings are conveyed to us (almost) only by what we can see from the outside.

In other words, we’re seeing like the camera sees.

No interior monologues.

No statements or descriptions of emotion.

There’s not even any dialogue.

The passage is powerful because we, the readers, are compelled by the writer’s technique to participate in the drama. We see the men silent, the women watching, the children tracing in the dirt with their toes. We see the expressions on the men’s faces and we think (we can’t help but think), These families are at the brink. Their land is drying up, their crops are dying. They are close to panic, close to giving in.

But no one states this overtly.

Not the characters and not the narrator.

We the readers supply all of that ourselves.

What makes movies so powerful when they’re done right is that they can show us faces and postures (i.e. non-verbal cues) and make us read emotion into those cues. We think to ourselves, Jackson Maine (Bradley Cooper) is falling in love with Ally (Lady Gaga) in the drag club scene in A Star is Born, even though he hasn’t yet said a direct word or made the slightest romantic move in her direction.

We see it in his eyes and hear it in his voice.

Steinbeck was a master at portraying emotion on the printed page, not by overt statement or in dialogue but by describing the scene and the action from the outside, the way a camera would see it—the motion and the stillness and the hesitation and the action of the characters.

You and I can do it too, in our books and our plays.

We can write them (or at least parts of them) like a movie.

I put the mail on the table, went back to the bedroom, undressed and had a shower. I was rubbing down when I heard the door-bell pull. I put on a bathroom and slippers and went to the door. It was Brett. Back of her was the count. He was holding a great bunch of roses.

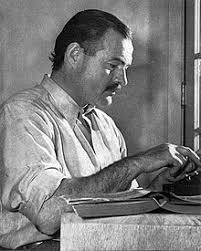

There’s a reason why Ernest Hemingway won the Nobel Prize and it wasn’t just because he used short words.

Ernest Hemingway picked up the prize in 1954

Hemingway taught himself to write not only the way the camera sees, but the way the eye sees. And he taught himself how to use this.

It was Brett. Back of her was the count. He was holding a great bunch of roses.

It may seem on first reading as if no particular emotion is being conveyed in this passage. What’s happening, we may think, is only the magic of black marks on paper creating a cinematic image in our mind.

But if we look a little closer …

We see the door opening.

We see Brett.

Then we see the count.

Then we see the great bunch of roses.

That’s exactly the way the eye works, isn’t it? It’s precisely the order and sequence of the way you or I, opening the door of our flat in Paris, would see someone standing there, then another person standing behind them, then whatever that second person happened to be carrying.

But what Hemingway does is show us this through the eyes of our narrator, Jake Barnes (who’s in love with Brett but whose manhood has been shot away in the war), who wants on this particular evening only to be left alone after his shower and now is being summoned forth by the obligation of good fellowship to a night of drinking and carousing that is going to tear his guts up.

All this in six short sentences with no dialogue and no overt expression of emotion.

Write it like a movie.

You’re hooking me with your line: “The [Steinbeck] passage is powerful because we, the readers, are compelled by the writer’s technique to participate in the drama.”

I’m thinking again of “the beholder’s share” (term from art historian Alois Riegl): you have a painting, but that painting is not complete until the viewer responds to it. Here’s a cool (5-min) talk by Eric Kandel (another Nobel Prize winner, his was in 2000). He grabbed me with his brief discussion of why the Mona Lisa is considered one of the masterpieces of western art. He points to the ambiguity of her facial expression: Is she smiling or is she not? We’re EACH drawn in because we’re compelled to participate by engaging and wanting to understanding her. Since the beholder’s share varies for each of us, because we’re each bringing an element of our own creativity into it, we each derive our own meaning. We’re co-creating. Good Wednesday post.

https://youtu.be/IoubVUSk7h0

And a sidebar about Steinbeck while we’re on him. Yesterday I came across the letter he wrote to Marilyn Monroe in 1955, asking her for an autographed photo on behalf of his “nephew-in-law,” whom he described:

“He has his foot in the door of puberty, but that is only one of his problems. You are the other.”

He continues:

“Would you send him, in my care, a picture of yourself, perhaps in a pensive, girlish mood, inscribed to him by name and indicating that you are aware of his existence. He is already your slave. This would make him mine.”

Dude, THAT’s some prize-winning writing, right there.

Indeed! “He is already your slave. This would make him mine.”

Wow.

Terse, cogent brilliance is washed away in the tidal wave of “content” we try to navigate every day now. Thank you, Steven, thank you once again for serving up some brilliance yet again today.

Excellent Steven! Thank you. My cowriter and I learned this truth while turning our screenplay, “I am Keats,” into a novel (I know… backwards). Anyway, it forced us to see the story visually, which was a very helpful change of perspective.

Such a perfect reminder and efficiently stated. As always, thank you.

It takes factual description of what provokes the emotion or feeling to recreate it in another – feeling isn’t conveyed by just stating the feeling – it requires a clear succinct concise description of whatever it is that causes it – then there’s a chance the same inner state will be induced in the reader.

Agreed.

I’d argue that what gives the Steinbeck passage its power is not what the camera would see, but the two explicit indications of what meaning the women are making, in other words, their interiority: “to feel whether this time the men would break” and “Then the women knew that they were safe and that there was no break.” What’s more, the emotion in the men’s faces is labelled, it doesn’t just describe what you’d see, but the internal emotion signified (anger / bemused perplexity). Emotions and interiority are very explicitly stated and that is what lends meaning and power to the visual, physical details.

Georgina, this is excellent analysis of what makes the pasage work. Thank you.

I am so happy to have been introduced to you via “London Real” and have read (and am re-reading, “The War of Art” and “Turning Pro” (which I have also shared with my 4,500 Facebook Friends). Today’s message is so valuable as it reminds me of something I posted on my website shortly after I began to paint (in July 2009). Thank you for confirming the validity of my own thoughts.

“I paint as if I am writing with brushes and color.

I write as if I am painting with words.”

When the student is ready…….I suppose my introduction to you confirms that I was ready for my “Next Step”.

This is fantastic and so helpful — thank you! Here’s a perfect example of why I look forward to these posts every week!

Great post thank you! I just rewrote a beginning scene in short words like this describing the scene and was wondering if I was being too spare with my words. When I taught in a graphic design school the phrase “less is more” was often heard. You have a confirmed this in yet another way.

“The men were silent and they did not move often. And the women came out of the houses to stand beside the men—to feel whether this time the men would break … The children stood nearby, drawing figures in the dust with bare toes … ”

For me, the passage, “The children stood nearby, drawing figures in the dust with bare toes…” has a power of its own. Steinbeck doesn’t describe the children, what they wear, etc… Yet, what immediatley comes to mind are little boys and girls dressed in rags, malnourished, dusty yet somehow content for the moment. Sometimes more is less.

Thank you for a great post!

Now, I’m off to “write it like a movie.”

When I was first reading Steinbeck I was dating a photographer and learning about qualities of light. I had thought light was just air and that’s just clear. As I was beginning to see different lights there was Steinbeck deftly describing a quality of light. He could see and then show me. The man is amazing!

As the sun dipped below the horizon, casting a warm, golden glow across the picturesque garden, the scene was set for the most magical moment of Sarah and John’s lives. The gentle hum of conversation faded as the soft strains of their favorite song, “Can’t Help Falling in Love,” filled the air, and all eyes turned toward the beaming couple standing at the altar. It was a scene straight out of a romantic movie, where the choice of wedding song had the power to transport everyone present into the world of love and happiness. As the chorus swelled and their hearts beat in rhythm with the music, it was clear that this was the perfect choice for their special day, a sentiment shared by all who had gathered to witness this beautiful union. Wedding Songs have the remarkable ability to encapsulate the essence of a couple’s love story, and in that moment, Sarah and John’s choice had captured the hearts of everyone present, making it a day they would cherish forever.